News Details

by Lynn Chiu

On a hot summer afternoon, Nicole Grunstra and I sat down to talk about a puzzling feature of pregnancy and birthing, one that – on the face of it - separates us, humans, from our primate cousins. After pointing to images in her latest paper depicting the descent of the fetus through the pelvis’ birth canal in a chimpanzee, Nicole shaped her hands into a big “O.”

“For other primates, it’s a relatively straightforward process,” she said. “The newborn tunnels right out.” I imagine myself peering into the chimpanzee birth canal as I looked down at the figures. With the mother’s pelvic bones framing the skull of the chimp newborn-to-be like great wings of a bat, the baby looks almost gleeful as it goes “weeeee!” down the canal, sliding face forward.

Chimp baby going weeeeee! (image from fig 4 of original paper)

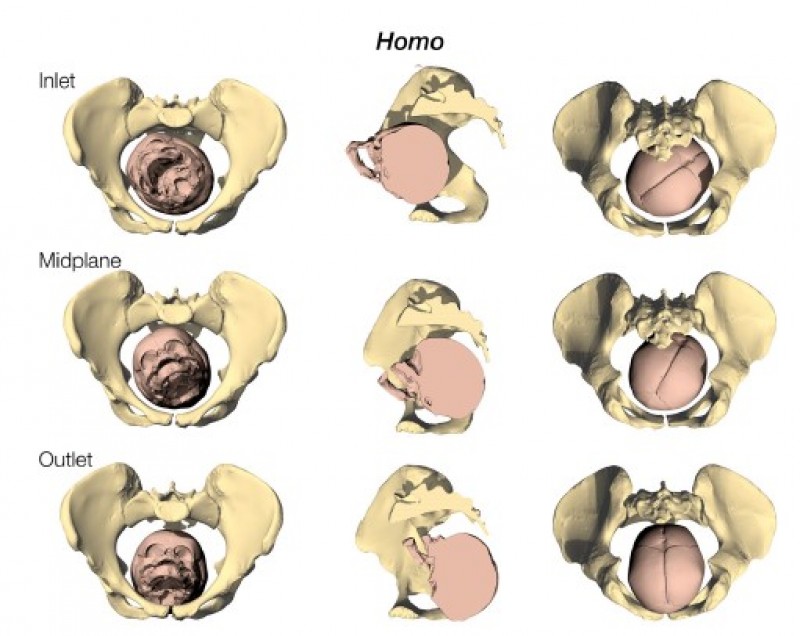

I laughed, then gasped as I followed her finger to the next set of images. What is this twisted torture that is the human birthing process? Cupping her hands into a horizontal oval, then a vertical oval, then a big “O”, Nicole described twists and turns in the canal that reminded me of the long, convoluted cave rescue mission in Thailand years ago. “Mechanistically, human birthing is a protracted, painful process compared to that of other primates.” The head must flex, reorient, squeeze, and change its shape, followed by the shoulders, as the mother’s pelvis guides the fetus while it burrows head-first through the bony birth canal, gasping for air at the end.

The twists and turns of the human birth canal. (image from fig 4 of original paper)

Why is birthing so difficult in humans and why is giving birth such a risky business?

Nicole’s new review in Biological Reviews carefully evaluates the so-called “Obstetrical Dilemma” hypothesis, a set of evolutionary claims about how our birthing process came to be comparatively difficult and risky and why our infants are born relatively helplessly. The dilemma arises from the evolutionary tradeoff between different functions of the pelvis. Unlike other primates and indeed most other mammals, we are bipedal—we walk straight on our two feet. To stabilize our trunk and facilitate our ability to walk upright, the pelvis needs to be narrow. Yet also unlike most other primates, our babies’ heads are relatively larger and thus require a wider or otherwise larger pelvis. Being pulled in different directions, our current pelvic configuration is thus an evolutionary compromise, one that is less than optimal in either regard.

Recently, the Obstetrical Dilemma (OD) hypothesis has come under significant challenge. For example, the claim that bipedal locomotion constrains evolutionary expansion of the pelvic (birth) canal has not found support in empirical studies. Furthermore, a perspective emphasizing maternal metabolic limits towards the end of pregnancy has challenged the notion that the pelvis imposes a constraint on the length of pregnancy, and thus the size of the fetus at birth. In light of these concerns, it is tempting to ditch the OD altogether. “One idea for our subtitle, instead of ‘there’s life in the old dog yet,’ was ‘let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater,’ but we thought that was a bit too much on the nose,” Nicole noted. So, in collaboration with Martin Haeusler, Nicole Webb and their team of colleagues, the authors decided to take a closer look at whether all avenues for the OD have been exhausted and crystallized the core biological, including evolutionary, processes that shape pelvic morphology— and consequently, the birth canal. (To get a fuller picture of the nuanced debates, I recommend pairing Dunsworth’s 2016 and 2018 reviews with this paper.)

“I am fascinated by how complex this is,” Nicole sat back to explain why pelvic evolution and the evolution of human childbirth became her main research topic, “to understand why childbirth is difficult, one must first consider the maternal and the fetal component. Obstructed labor depends on how tight the fetal-pelvic fit is, so either part of the fit will affect it! Secondly, both pelvic and fetal size are influenced by environment-development interactions as well, so the delicately tight fetopelvic fit is at risk of being thrown off balance by various factors, increasing the risk of complications.”

Unpacking the paper: what is the hypothesis and where did it come from?

I told Nicole that I itched to reach for popcorn while reading the first two sections. One not only gets an overall sense of how our biology and evolutionary history contributes to the difficulty of childbirth (and the drama involved in pinpointing exactly who or what is to blame), but also where the idea of OD, the Obstetrical Dilemma, came from. The origin story was a constellation of 20th-century ideas pulled together by Sherwood Washburn, who proposed it in a popular science article on brain evolution and tool use and which was not meant for the academic community (side note: an inspiration I, as a science communicator, hope to achieve one day). Somehow, as the piece was introduced into the anthropology literature, Washburn’s broad-stroke, imprecise narrative grew and splintered into different forms. Getting to the original sources and ideas and disentangling various conflated OD claims is one of the main goals of Nicole’s piece.

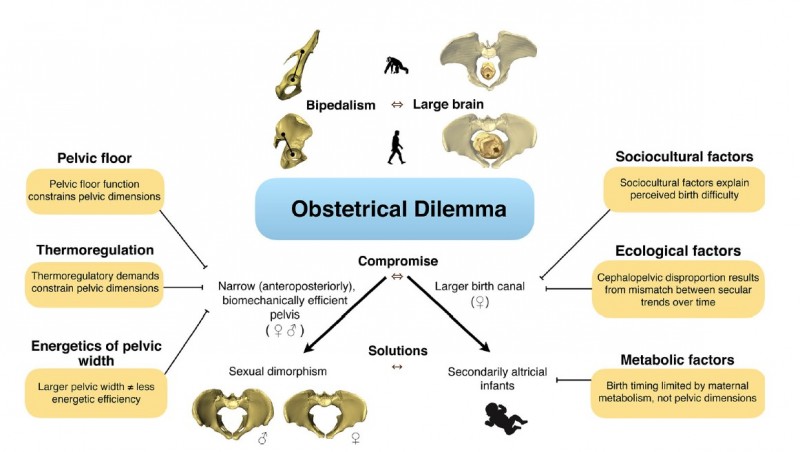

The authors break down the OD into four major components and the bulk of the paper analyzes these major components. The schematic figure below (Fig. 1 in the paper) summarizes these components and how they’re challenged. Starting from the middle, we can see the original dilemma, the compromise, including the precise functions underlying it, and two major evolutionary “solutions” that supposedly help achieve a relative optimum despite the dilemma: sexual dimorphism (the male sex is spared from the evolutionary constraint imposed by birthing while the female sex is subject to both) and secondary altriciality, or the birth of infants at an earlier, much more helpless developmental stage (so that their heads are still relatively small and can come out easier). Multiple types of explanations —mechanistic, developmental, physiological, ecological, social-cultural, or also evolutionary — challenge or indeed support or complement each component.

Schematic showing the original obstetrical dilemma hypothesis and complementary or alternative explanations (orange lozenges) as they relate to specific components of the obstetrical dilemma proposed by Washburn (1960). (Figure 1 of the original paper)

“The OD is not just a single hypothesis but multiple ideas that are not mutually exclusive. First of all, a tradeoff doesn’t have to exist between just bipedalism and childbirth, so a refutation of selection related to these functions does not mean that there are no other evolutionary constraints in the pelvis. For instance, the pelvic floor hypothesis states that the function of the pelvic floor also constrains pelvic dimensions, a hypothesis for which Nicole and her Viennese colleagues recently found experimental support. “Yet the entire OD tends to be criticized or refuted on the basis of one of these ideas being tested,” explained Nicole. “Secondly, the fact that there are many non-evolutionary factors influencing the fetal phenotype and the risk of obstructed birth does not refute that there are evolutionary constraints on the pelvis. They can be compatible.”

By reanalyzing the raw data in some cases (e.g. a study refuting the bipedalism hypothesis actually supports it), proposing new perspectives in others (e.g., conserved developmental pathways, especially in combination with more evolvable developmental ‘tweaks’, are compatible with adaptive scenarios), or clarifying evolutionary hypotheses in yet others (e.g., expanding which morphological aspects —mediolateral width or anteroposterior depth? – are examined as the relevant trait for bipedalism), Nicole and colleagues carefully and thoroughly went through the objections, and yet there still may be more stones left unturned. “Let’s hold off from throwing it out until we’ve thoroughly investigated all elements of the OD hypothesis. There are still lots of things to study there and many more versions and alternatives to test!”

Is there life in the OD (Old Dog) yet? Some take-home messages.

The ideas captured under the OD have developed and evolved over time. “I am not personally invested in most of the OD components, but many of them probably remained largely valid or deserving of further empirical study, although we have learned a lot more about how things work.” The OD is not and was never intended to be an exhaustive explanation of the complexity of human childbirth, pelvic evolution, and human ‘helplessness’ at birth. “The things we learn now do not necessarily discredit it but reinterpret it. Complexity does not discount the OD; the hypothesis and underlying evolutionary framework can continue to serve us, despite important additions and amendments.”

We hope that the reader can also appreciate how eye-opening it is to find tradeoffs everywhere. “There are tradeoffs to so many aspects of our morphology and to the birth process. For instance with regard to the pace of birth, if it’s too fast, the maternal pelvic floor tissues risk getting injured, yet if it’s too slow, the baby might end up in distress and the mother may be too fatigued to continue.” But finding more tradeoffs and selective explanations does not imply a “pan-adaptationist” viewpoint that attributes all phenotypes to past selection either. As Nicole elaborated, “the complexity of the evolution of childbirth opens up questions at many explanatory levels. There is great confusion about which ones are competitively exclusive or compatible. Inspired by Tinbergen’s four questions, the next step for me is to tell a fuller story by working out an organizational framework to fit these explanations together.”

Come and learn about the twists and turns of the history of the OD, the current debate, and the birth canal itself. The 27-page piece is elegantly structured into sections that allow for easy indexing. Nicole encourages the interested reader to jump to a section of specific interest for a more careful read, whereas the first two parts review the claim that human birth is in fact risky and the history of the ideas combined under the OD, and the last one—the “outlook” and “conclusions” sections outline the main message and outcomes of the paper.

As for me, what did I get from this interview? From now on I can never think of my own birth canal in the same way again. It is as if I was once again learning that duck penises are the shape of corkscrews. It, and the theories behind it, are all twisted now.

Publication

Haeusler, M., Grunstra, N. D. S., Martin, R. D., Krenn, V. A., Fornai, C., & Webb, N. M. (2021). The obstetrical dilemma hypothesis: There’s life in the old dog yet. Biological Reviews https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12744